Since inviting a new enforcement chair to the Bloomsbury CAAC two thorough surveys of buildings on Gray’s Inn Road and Marchmont Street have been conducted to investigate planning breaches, mainly pertaining to shopfronts.

Shopfronts are typically the subject of most planning breaches due to poor levels of awareness about planning and advertisement law among shopkeepers and owners.

It was found that more than 80% of surveyed buildings had been the subject of illegal alterations, with an astonishing 21 consecutive buildings on Gray’s Inn Road having been subject to planning breaches.

A large proportion of these breaches had been committed more than 4 years ago making them ‘legalised’. Their reversal is now almost impossible.

Many businesses with open planning applications had made the requested changes despite not having received any decision. And others, including major corporations like KFC and Currys, had made their alterations before putting in a planning application.

It means that the tens of thousands of hours spent by planners, councillors, and conservationists in formulating and applying planning policy to planning applications over the past decade appears to be largely in vain, as adhering to planning law is increasingly becoming optional.

But despite the new Enforcement Panel having made a total of 42 reports over the past four months, Camden have only officially acknowledged two of those, and have stated they do not have the capacity to take on any ‘enforcement projects’ at the current time.

But beyond the majority of ‘minor’ alterations made to shopfronts and building facades that have gone unnoticed, a number of severe planning breaches relating to Grade II and Grade I listed buildings have been committed with no apparent enforcement action planned.

In 2013 an entire colonnade was illegally demolished opposite the Grade I listed St George’s Bloomsbury before planning permission was granted for redevelopment of the building. Camden’s planning committee subsequently granted permission for the works making their reinstatement impossible.

It was discovered earlier this year that all the historic railings of the Grade I listed 40 Bedford Square had been sawn off at the base. A hoarding had previously been erected to hide the works being undertaken. But despite repeated requests for clarification it appears no enforcement has been taken.

A number of weeks ago the wholesale removal of original Georgian sash windows at Grade II listed 12 Leigh Street was noticed by a Bloomsbury CAAC member. Swift action led to the apparent halting of works but a number of Georgian windows had already been removed from the site.

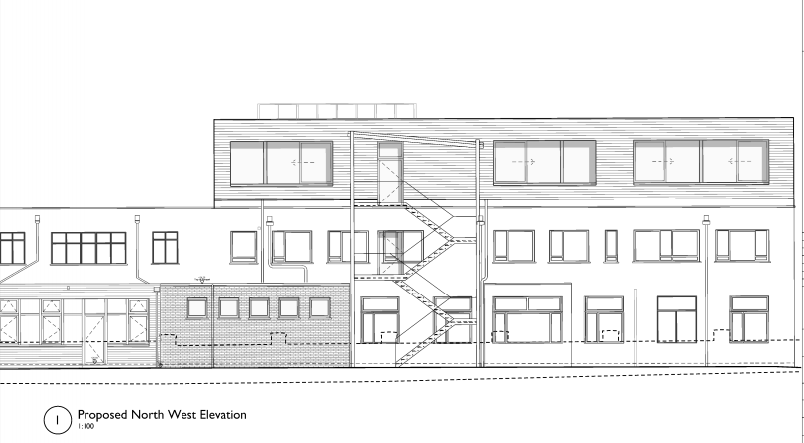

Last month an emergency report of the substantial demolition of a Georgian terrace at 289 Gray’s Inn Road led to no immediate enforcement action, although it has been promised that ‘a report will be opened’ after a number of emails urging an emergency site visit were ignored.

Members of the community, leading conservation officers and consultants, national amenity societies, and local conservation groups have all lambasted a ‘lazy’ service for consistently ignoring emails instead of acknowledging and processing complaints in accordance with the constitution and wider planning law and policy.

Camden’s Local Enforcement Plan 2020 states all complaints will be acknowledged within 5 working days and a site visit undertaken within a maximum of 15 working days. But some complaints have still not been acknowledged despite having been made more than a year ago. Subsequent planning applications have been made citing these illegal alterations as precedent.

And while Camden has committed to maintaining a public open register of enforcement notices, the website where these are hosted has not worked for several years.

Glenda Davies from Sandwich Street made repeated reports of illegal alterations to the Lutheran Centre on the same street. But Camden’s enforcement officer ignored several emails and responded making incorrect claims about planning law, eventually closing the case without any action. An enforcement case was reopened after the Bloomsbury CAAC and Twentieth Century Society wrote a joint letter in support of Glenda Davies’ complaints, but subsequently closed again with a planning officer stating the case was ‘not expedient to pursue’.

A breach of planning law is a serious criminal offence. Unauthorised works to a listed building can result in an unlimited fine or up to two years’ imprisonment. This makes it an offence more severe than common assault, which only carries a six month imprisonment sentence and a fine of up to £10,000.

Camden have claimed that they simply do not have the capacity to deal with the volume of enforcement breaches throughout the borough. Enforcement officers have reported having up to 100 cases to investigate at any one time.

But repeated offers from the Bloomsbury CAAC to help shoulder the burden of mundane work such as surveying areas, investigating breaches, writing notices, and liaising with building owners have been ignored.

Camden’s enforcement team has offered a meeting in November to discuss the 42 reports made over the past four months. But whether this will result in any tangible difference to the current state of enforcement inaction remains to be seen.

Two meetings have already been held between the Bloomsbury CAAC and Camden’s Enforcement Team over the past 2 years to report about 15 breaches as a trial. But of those, only one was actioned and the owner subsequently reversed the changes after only a month.

Marianne Jacobs-Lim of the Bloomsbury CAAC stated: ‘Camden is guilty of negligence and is sanctioning crime by inaction. These are serious crimes, yet there is a dreadful feeling that Camden’s internal court has pushed them into a misdemeanour category. Addressing crime, solving crime, and punishing crime must happen regardless of any excuses and needs to become an absolute priority.‘

Catherine Croft, director of the Twentieth Century Society stated: ‘A planning system with no sanctions is worthless. It’s bad enough that building owners and developers know that fines for breaching planning conditions or carrying out works without permission are ludicrously low, throughout the country, but this research is shocking. The detrimental impact of small changes builds up over time, and the quality of buildings is soon lost, making our streets less interesting and inspiring for everyone. A properly resourced planning system makes where we live and work better for everyone.‘

Round-the-clock work by planners and conservationists is becoming increasingly farcical as recent enforcement surveys indicate the majority of buildings in Bloomsbury have been illegally altered over the past ten years.

Since inviting a new enforcement chair to the Bloomsbury CAAC two thorough surveys of buildings on Gray’s Inn Road and Marchmont Street have been conducted to investigate planning breaches, mainly pertaining to shopfronts.

Shopfronts are typically the subject of most planning breaches due to poor levels of awareness about planning and advertisement law among shopkeepers and owners.

It was found that more than 80% of surveyed buildings had been the subject of illegal alterations, with an astonishing 21 consecutive buildings on Gray’s Inn Road having been subject to planning breaches.

A large proportion of these breaches had been committed more than 4 years ago making them ‘legalised’. Their reversal is now almost impossible.

Many businesses with open planning applications had made the requested changes despite not having received any decision. And others, including major corporations like KFC and Currys, had made their alterations before putting in a planning application.

It means that the tens of thousands of hours spent by planners, councillors, and conservationists in formulating and applying planning policy to planning applications over the past decade appears to be largely in vain, as adhering to planning law is increasingly becoming optional.

But despite the new Enforcement Panel having made a total of 42 reports over the past four months, Camden have only officially acknowledged two of those, and have stated they do not have the capacity to take on any ‘enforcement projects’ at the current time.

But beyond the majority of ‘minor’ alterations made to shopfronts and building facades that have gone unnoticed, a number of severe planning breaches relating to Grade II and Grade I listed buildings have been committed with no apparent enforcement action planned.

In 2013 an entire colonnade was illegally demolished opposite the Grade I listed St George’s Bloomsbury before planning permission was granted for redevelopment of the building. Camden’s planning committee subsequently granted permission for the works making their reinstatement impossible.

It was discovered earlier this year that all the historic railings of the Grade I listed 40 Bedford Square had been sawn off at the base. A hoarding had previously been erected to hide the works being undertaken. But despite repeated requests for clarification it appears no enforcement has been taken.

A number of weeks ago the wholesale removal of original Georgian sash windows at Grade II listed 12 Leigh Street was noticed by a Bloomsbury CAAC member. Swift action led to the apparent halting of works but a number of Georgian windows had already been removed from the site.

Last month an emergency report of the substantial demolition of a Georgian terrace at 289 Gray’s Inn Road led to no immediate enforcement action, although it has been promised that ‘a report will be opened’ after a number of emails urging an emergency site visit were ignored.

Members of the community, leading conservation officers and consultants, national amenity societies, and local conservation groups have all lambasted a ‘lazy’ service for consistently ignoring emails instead of acknowledging and processing complaints in accordance with the constitution and wider planning law and policy.

Camden’s Local Enforcement Plan 2020 states all complaints will be acknowledged within 5 working days and a site visit undertaken within a maximum of 15 working days. But some complaints have still not been acknowledged despite having been made more than a year ago. Subsequent planning applications have been made citing these illegal alterations as precedent.

And while Camden has committed to maintaining a public open register of enforcement notices, the website where these are hosted has not worked for several years.

Glenda Davies from Sandwich Street made repeated reports of illegal alterations to the Lutheran Centre on the same street. But Camden’s enforcement officer ignored several emails and responded making incorrect claims about planning law, eventually closing the case without any action. An enforcement case was reopened after the Bloomsbury CAAC and Twentieth Century Society wrote a joint letter in support of Glenda Davies’ complaints, but subsequently closed again with a planning officer stating the case was ‘not expedient to pursue’.

A breach of planning law is a serious criminal offence. Unauthorised works to a listed building can result in an unlimited fine or up to two years’ imprisonment. This makes it an offence more severe than common assault, which only carries a six month imprisonment sentence and a fine of up to £10,000.

Camden have claimed that they simply do not have the capacity to deal with the volume of enforcement breaches throughout the borough. Enforcement officers have reported having up to 100 cases to investigate at any one time.

But repeated offers from the Bloomsbury CAAC to help shoulder the burden of mundane work such as surveying areas, investigating breaches, writing notices, and liaising with building owners have been ignored.

Camden’s enforcement team has offered a meeting in November to discuss the 42 reports made over the past four months. But whether this will result in any tangible difference to the current state of enforcement inaction remains to be seen.

Two meetings have already been held between the Bloomsbury CAAC and Camden’s Enforcement Team over the past 2 years to report about 15 breaches as a trial. But of those, only one was actioned and the owner subsequently reversed the changes after only a month.

Marianne Jacobs-Lim of the Bloomsbury CAAC stated: ‘Camden is guilty of negligence and is sanctioning crime by inaction. These are serious crimes, yet there is a dreadful feeling that Camden’s internal court has pushed them into a misdemeanour category. Addressing crime, solving crime, and punishing crime must happen regardless of any excuses and needs to become an absolute priority.‘

Catherine Croft, director of the Twentieth Century Society stated: ‘A planning system with no sanctions is worthless. It’s bad enough that building owners and developers know that fines for breaching planning conditions or carrying out works without permission are ludicrously low, throughout the country, but this research is shocking. The detrimental impact of small changes builds up over time, and the quality of buildings is soon lost, making our streets less interesting and inspiring for everyone. A properly resourced planning system makes where we live and work better for everyone.‘