Recent events at St George’s Gardens show how planning should and does work when there isn’t a great deal of money involved.

The BCAAC has recently been involved in an exemplary piece of work of collaboration between ourselves, Camden, a developer, and another community group at St George’s Gardens, in the Bloomsbury CA.

It demonstrates exactly how planning should work at all times. It is unfortunate that planning only works this well for small applications across our CAs, while larger applications adopt more of a ‘brute force’ approach. Some of the reasons for this are touched on in the following article, written by one of our members, Owen Ward.

The original article can be found on Save Bloomsbury.

Usually the word ‘planning’ in Camden is associated with the demolition of Victorian and Georgian buildings, consultation responses being ignored, residents being belittled as ‘Nimbys’, and utterly disgusting buildings being erected in the name of ‘progress’. And this week there is a new story involving the usual suspects: planners, developers, conservationists, and community groups, but rather than being pitted against one another, surprisingly enough they have been working together.

Once upon a time during the sleepy summer of 2020, in a BCAAC meeting I was tasked with investigating and formulating a response to a new planning application on the Coram campus, overlooking St George’s Gardens.

St George’s Gardens in recent years has managed to cultivate fairly good development around it. The Old Dairy to the north is quite an inoffensive development, not exactly ‘Bloomsbury’ but domestically sized, easy on the eye, and respecting the setting of the gardens and the listed properties to the north of it. To the east a new development on ‘Westking Place’ is quite appropriate, a sort-of modern take on Georgian terraces, not exactly awe-inspiring but again respecting St George’s Gardens and the wider CA.

The new application was to redevelop an old modern building overlooking the gardens, itself quite an ugly building and in poor repair, more appropriate to run-down Birmingham than Bloomsbury. It was the last frontier of redevelopment facing onto the square – every other site earmarked for redevelopment had been completed.

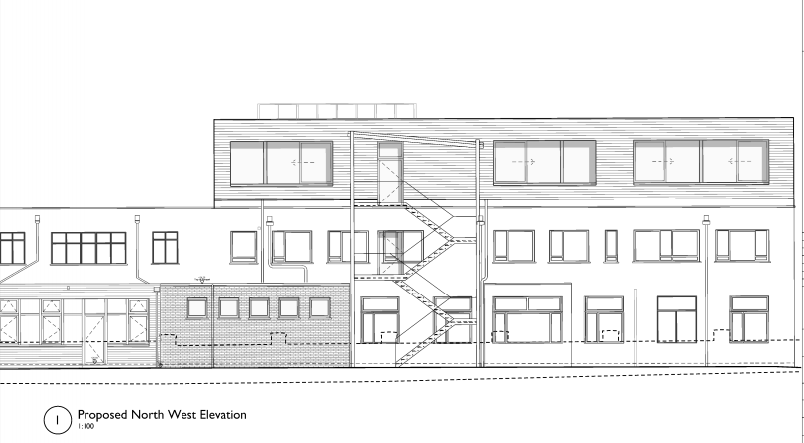

The proposal was to completely redevelop in two phases. Rather than demolish the existing building, it would see an extension to the front and then a further rooftop extension overlooking the gardens. So for the BCAAC, the priorities were twofold – to ensure the development as a whole enhanced (or at least preserved) the Bloomsbury CA, and that the redevelopment opportunity was grasped to ensure a much improved rear elevation onto St George’s Gardens.

Unfortunately the planning application left much to be desired as it stood. The front elevation, while in itself not offensive, was unbalanced by the use of a range of different materials, some quite strange and certainly not drawn from the CA. Then the rooftop extension overlooking the gardens appeared to pay no regard to the existing building whatsoever, not doing anything to alter the existing elevation, and even introducing a steel staircase. Oh dear, I thought, what a shame.

I contacted the planner, Kristina Smith, to raise my concerns, but she indicated that she preferred it if I did not raise an objection on the BCAAC’s behalf as this would introduce potentially significant time delays. A BCAAC objection automatically ‘escalates’ any small planning application like this one, potentially putting it to full committee hearing and delaying determination of the application for months. Instead I offered to liaise with the developers on the design to see if some alterations could be made to the main facade and especially rear elevation.

Eventually I got in touch with the architect Phil Meadowcroft, from Phil Meadowcroft Architects, and talked with him on the phone while in the gardens about potential changes that could be made. I expressed that refacing the rear elevation in brick would be preferable given that every other building facing the gardens was in London stock. He said that as Coram were a charity, however, it would be difficult to justify the extra expense simply for aesthetic reasons. I suggested whether instead the rear elevation could be ‘greened’, which seemed to be a preferred option. We also talked about ‘rationalising’ the front elevation to only use white render and London stock, similar to many of the Georgian terraces in the area, whose ground floor is white render with upper storeys London stock.

We agreed to meet in the gardens to discuss at a future date, and to involve the Friends of St George’s Gardens.

A week or so later the BCAAC chairman Hugh Cullum and Ian Brown from the Friends of St George’s Gardens met with architect Phil Meadowcroft in the gardens (socially distanced, of course) to discuss the proposals.

It was agreed that the rear elevation would be greened by means of trellises and climbing plants, while the elevation overlooking St George’s Gardens would also be ‘cleaned up’, with the existing render being repaired and painted white, and some defunct wiring and pipework being removed. This would certainly greatly improve the setting of St George’s Gardens.

The architect went away and had a number of conversations with Coram with the aim of revising the front elevation in light of BCAAC comments, and eventually came back with a far better design, constructed in only white render and London stock as previously requested.

Although London stock on ground floor and white render on upper floors is ‘upside down’ compared to the Georgian heritage of the area, it certainly represents an improvement and the facade appears much more ordered and architecturally linked to the surrounding area.

Following these revisions I agreed to withdraw the BCAAC’s informal objection so that the application could be approved.

While a simple and unexciting story, it shows how planning consultation can and should be done in Bloomsbury. The development proposal affected the Bloomsbury CA and St George’s Gardens, so the Bloomsbury CAAC and Friends of St George’s Gardens raised their concerns, and the developers went away with the express purpose of resolving these concerns. The developer then came back with a different proposal and even showed evidence of considering multiple different proposals in these efforts. The new proposals were judged an improvement and to enhance the Bloomsbury CA and so the BCAAC rescinded their objection, and all was well.

Two things aligned correctly for this to happen.

Firstly, it being a ‘small’ application, a BCAAC objection carries quite some weight as it takes a planning application out the hands of the planner delegated to determine the application. This introduces possibly unnecessary and unwanted scrutiny, lengthy time delays, and possibly even a refusal at committee. The fact that a BCAAC objection carries weight means that once an objection was floated, the planner wanted to work to resolve the objection.

Secondly, the desire shown by the planner to resolve the objection, coupled with the respect of the developer for planner and BCAAC alike meant that they were willing to go away and work to come back with an improved proposal.

For larger applications, neither of these things are the case.

Firstly, a large application automatically goes to planning committee, and so while a BCAAC objection technically does carry weight, it doesn’t actually do anything to make the planner’s life more difficult. So it is easy enough for planners to simply ignore our objections.

Secondly, the fact that planners don’t respect our objections means that developers tend not to care either, and certainly don’t go away looking to resolve the objection. And while large developers tend not to respect the BCAAC, it is not necessarily the case that they even respect Camden – so even a planner wishing to resolve our objections may not have the power to get a developer to consider a redesign.

Should the BCAAC’s objections carry greater weight in the face of large development? Probably. But as things currently stand, even Historic England are routinely ignored by Camden’s planners. Yet fairly often the BCAAC actually gives more detailed and informed feedback than Historic England, while knowing Camden and Bloomsbury far better – perhaps we should be taken more seriously than HE. Certainly a desire to resolve BCAAC objections would lead to an all round healthier planning system, one more mindful of Central London’s heritage and wellbeing as a whole. But actually getting big shot planners and councillors to take CAAC comments seriously is a tall order.

The only way to really make an impact is to campaign well enough to get applications refused regardless of planner recommendation, as the BCAAC did with the British Museum.

But beyond all the abstract theorising, the community involvement of this story in the planning system has led to a development which will now enhance St George’s Gardens and Bloomsbury when before it would have damaged both – and that is a success. It shows that when the community are properly engaged in planning matters, it does lead to better outcomes for all involved.